111581649901

Untitled

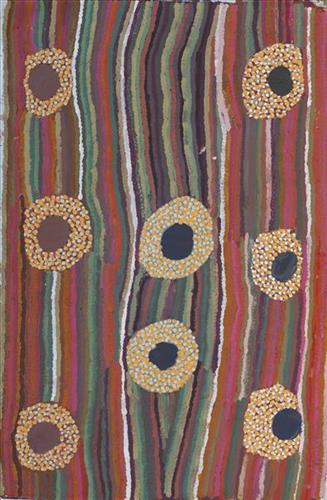

“When Martu paint, it’s like a map. Martu draw story on the ground and on the canvas, and all the circle and line there are the hunting areas and different waters and tracks where people used to walk, and [some you] can’t cross, like boundaries. So nowadays you see a colourful painting and wonder what it is, but that’s how Martu tell story long ago. It’s not just a lovely painting, it’s a story and a songline and a history and everything that goes with it.”

– Ngalangka Nola Taylor and Joshua Booth

This work portrays an area of Country that can be interpreted in multiple ways. Firstly, the image may be read as an aerial representation of a particular location known to the artist- either land that they or their family travelled, from the pujiman (traditional, desert dwelling) era to now. During the pujiman period, Martu would traverse very large distances annually in small family groups, moving seasonally from water source to water source, and hunting and gathering bush tucker as they went. At this time, one’s survival depended on their intimate knowledge of the location of resources; thus physical elements of Country, such as sources of kapi (water), tali (sandhills), different varieties of warta (trees, vegetation), ngarrini (camps), and jina (tracks) are typically recorded with the use of a use of a system of iconographic forms universally shared across the desert.

An additional layer of meaning in the work relates to more intangible concepts; life cycles based around kalyu (rain, water) and waru (fire) are also often evident. A thousands of year old practice, fire burning continues to be carried out as both an aid for hunting and a means of land management today. As the Martu travelled and hunted they would burn tracts of land, ensuring plant and animal biodiversity and reducing the risk of unmanageable, spontaneous bush fires. The patchwork nature of regrowth is evident in many landscape works, with each of the five distinctive phases of fire burning visually described with respect to the cycle of burning and regrowth.

Finally, metaphysical information relating to a location may also be recorded; jukurrpa (dreaming) narratives chronicle the creation of physical landmarks, and can be referenced through depictions of ceremonial sites, songlines, and markers left in the land. Very often, however, information relating to jukurrpa is censored by omission, or alternatively painted over with dotted patterns.