111582324481

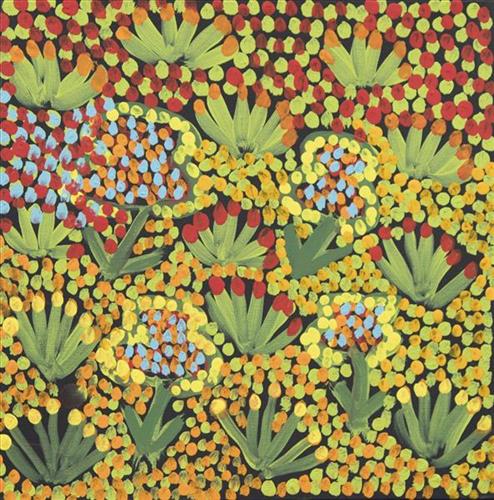

Wildflowers

“Flower after the rain, you know- a mix. Blue, pink, yellow and purple- grow up with the grass after the rain. You can see anywhere when the burnt ground grows after the rain. [On] old nyamu (my grandfather’s) burnt Country.”

– Ngarga Thelma Judson

In this work Thelma celebrates the aesthetic splendour of desert flowers in her grandfather’s ngurra (home Country, camp).

In the context of the often harsh and arid environments in which desert flowers thrive, their vibrancy, delicacy, and variation become even more spectacular. At the same time, she acknowledges the phenomenon of the desert flowers blooming in relation to the Martu cycle of burning and regrowth and its five distinct phases. First is nyurnma (freshly burnt Country), followed after the rains by waru-waru, when young, bright green plants start to grow. Nyukura occurs between one and three years after burning, when plants have matured and are fruiting and seeding. Manguu is four to six years post burning, when spinifex has matured to the point that it can be burned once again. Finally, kunarka signifies the time when spinifex and other plant species have become old growth and pose a risk of destructive bushfires.

Thelma Judson’s grandfather’s Country is Yimiri. Yimiri comprises two soaks situated in the middle of a salt lake in the Percival Lakes area, within Western Australia’s Great Sandy Desert. Around the waterhole the Country is dominated by tuwa (sandhills). When visiting this site to drink water, the plants and warta (trees, vegetation) growing in the kapi (water) are cleaned out as a way of maintaining the site.

During the pujiman (traditional, desert dwelling) days, Ngarga and her family travelled extensively through this county, their ngurra (home Country, camp). Her family moved up and down through this Country between water sources. When it was raining, they would build a wuungku (shelter) where they could sleep and stay warm beside a waru (fire). When they camped in a particular location for a period the elders would go hunting, leaving the children behind. Ngarga fondly recalls playing around in the tuwa in this region, catching parla-parla (type of lizard).

Yimiri is home to an ancestral jila (snake). The Western Desert term jila is used interchangeably to describe springs considered to be ‘living’ waters and snakes, both of which play a central role in Martu culture and Jukurrpa (Dreaming). During the pujiman period, knowledge of water sources was critical for survival, and today Martu Country is still defined in terms of the location of water sources. Of the many permanent springs in Martu Country, very few are ‘living waters’; waters inhabited by jila. Before they became snakes, these beings were men who made rain, formed the land and introduced cultural practices like ceremonies and ritual songs. Some of the men travelled the desert together, visiting one another, but they all ended their journeys at their chosen spring alone, transformed into a snake. These important springs are named after their jila inhabitant, guarding their waters.

The region surrounding Yimiri was formed by Wirnpa, one of the most powerful of the ancestral jila (snake) men and the last to travel the desert during the Jukurrpa. Wirnpa is a rainmaking jila who lived and hunted in the Percival Lakes area. His travels are described in the songs and stories of many language groups across the Western Desert, even those far removed from his home site. In his epic travels, Wirnpa met and feasted with many other ancestral beings, exchanged ceremonial objects, and created a series of different laws and ceremonies. When he finally returned home, he searched for his many children only to discover that they had already died. They had laid down and become the salt springs of the Percival Lakes. Wirnpa wept for his children before himself transforming into a snake and entering the soak where he still resides.