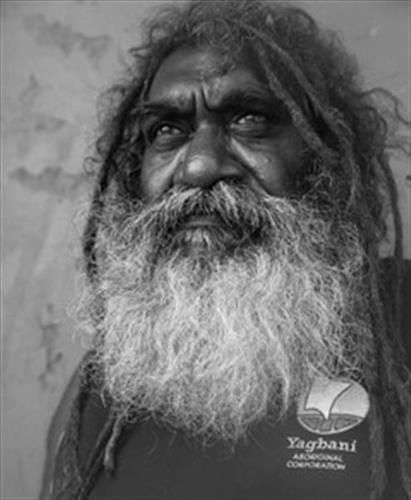

111982009342

Ngalkodjek Yawkyawk

This artwork depicts the Ngalkodjek Yawkyawk of Barrihdjowkkeng country.

“This story is very old. That old man [my father Crusoe Kuningbal] when he was alive, told that story to me, to all of us. He told us about the yawkyawk (mermaid) spirit women called Ngalkodjek who lives in the billabong on my country. He told us how they call out loudly, how they call out as they walk along.

That is what they do, calling out. They walked around eating bush foods like those little bush yams. They would pound the yams into a pulp and eat them. That is their traditional food which they eat.

When they walk down from the bush, they follow a set path that belongs to them and they walk along calling out. That is their path which they take. It is an old traditional route.

They placed a woman’s breast into the country. That rock was not there originally, but it was a woman’s breast. It is the breast of those women.

They put that djang [sacred place] there, and then at the time when non-Aboriginal people arrived in the region, then the breast turned to stone. Now it has turned solid into rock.”

– Owen Yalandja