111582121880

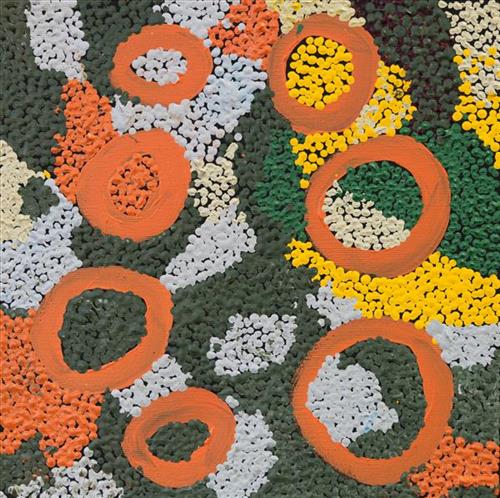

Parnngurr Rockhole

“Bugai [Whyoulter] told us to go back towards Parnngurr [with the intention of going into Jigalong mission], and we all went together along the track towards Parnngurr. In the afternoon we were going along, getting water for ourselves and walked over a sandhill. On the other side of the sandhill were a lot of vehicles: there was a bulldozer in front, then a grader and then several Land Rovers. We dropped everything and started to run. Old Man Biljabu [Jakayu’s husband] stopped and got ready to kill the whitefellas with his maparn [invisible power]. The whitefellas were waving in a friendly way and we all called out to Old Man Biljabu, “Stop! Stop! Don’t do it!” Jakayu and her husband started to walk towards the whitefellas. Everyone else followed behind them, starting to walk slowly.

We went and met the whitefellas and started talking to them, but they couldn’t understand us… The whitefella told us to go back to our camp and he would come and bring us food. After a time, he came and gave us a whole sheep, and some flour, sugar, bread and fruit. We threw the sheep away [for fear it might be poisoned] and left all the other food except for the sugar. We didn’t boil the sugar in the water with the tea, we just stirred it into warm water and drank it, like we did with bush tucker [edible botanical gum]. We used some of the flour to make a wet dough and drizzle it onto the ashes, the way we cooked seed damper. We didn’t finish eating the food – we just got up and went to Wiirnukurrujunu for pencil yams. We saw other Martu family groups pass by on the far side.

[Later, ] the whitefella followed us and found us where we were asleep… He went back to the mission to get Martu people who could translate. He went back to Jigalong and told Bob Ward, an old man, Sam Kelly’s father. He and Mr. Ward tracked us all the way to Yulpu and got there in the afternoon.

That day, everyone had gone hunting, and when we came back to our camp, there were four or five Land Rovers there. Mum had gone hunting early in the morning, carrying water with her. All us kids had gone west from Yulpu, and we had got one big goanna between all of us. When we came back in the afternoon, we saw that the whitefellas were in our camp, waiting for us. Us kids walked over slowly… When we came closer, Mr Ward opened a box and gave us blankets, clothes and food. He asked us where the others were, and we told him that they had gone over the hill. He told us to follow them and to call them back, and to come back all together and to wait at the road building camp. We agreed to do this. He told all us kids, “This is one blanket for all of you, you have to share it.” But we didn’t take the blanket. We kept walking with no clothes on, we left it there, no clothes, no blanket, didn’t even take the dresses.

We followed our parents over the hill… We spent the night with them and then went back to the place where we had been spotted [originally, at Parnngurr rockhole]. We waited there for the whitefellas to come back. When they arrived, they said that they had left their truck in between Parnngurr and Jigalong because it couldn’t go over the sandhills. The whitefellas were coming to get us in the Land Rover, taking three of us at a time, over to where the truck was waiting. From there they were carting all the people back to the truck. We all got in the truck and went right up to Old Jigalong, got there in the night time. That’s all.”

– Ngamaru Bidu, as translated by Ngalangka Nola Taylor

Parnngurr rockhole is located just south of Parnngurr Aboriginal community. This site lies within Ngamaru’s ngurra (home Country, camp), the area which she knew intimately and travelled extensively with her family in her youth. For many Martu, including Ngamaru, Parnngurr also signifies the location at which their nomadic bush life came to an end. Poignantly described here by Ngamaru, it was here that a group of 29 Martu were picked up by the Native Welfare Department to be taken to Jigalong Mission in 1963. Collectively the group had come to the decision to move to the mission as a result of an extended drought, which had caused a scarcity in food and water resources. The group also wanted to join their families, who had already moved to Jigalong.

At the junction of three linguistic groups; Manyjilyjarra, Kartujarra, and Warnman, Parnngurr rockhole was a critical and permanent source of water during the pujiman (traditional, desert born) era that supported many ritual large gatherings. During this nomadic period families stopped and camped here depending on the seasonal availability of water and the corresponding cycles of plant and animal life on which hunting and gathering bush tucker was reliant. At Parnngurr and other similarly important camp sites families would meet for a time before moving to their next destination. Parnngurr and its surrounds are physically dominated by distinctively red tali (sandhills), covered sparingly with spinifex and low lying shrub.

Parnngurr is also an important site chronicled in the epic Jukurrpa (Dreaming) story of the Jakulyukulyu, or Minyipuru (Seven Sisters). The sisters stopped to rest on Parnngurr Hill before continuing on their long journey east. Minyipuru is a central Jukurrpa narrative for Martu, Ngaanyatjarra, Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara people that is associated with the seasonal Pleiades star constellation. Relayed in song, dance, stories and paintings, Minyipuru serves as a creation narrative, a source of information relating to the physical properties of the land, and an embodiment of Aboriginal cultural laws. Beginning in Roebourne on the west coast of Western Australia, the story morphs in its movement eastward across the land, following the women as they walk, dance, and even fly from waterhole to waterhole. As they travel the women camp, sing, wash, dance and gather food, leaving markers in the landscape and creating landforms that remain to this day, such as groupings of rocks and trees, grinding stones and seeds. During the entirety of their journey the women are pursued by a lustful old man, Yurla, although interactions with other animals, groups of men, and spirit beings are also chronicled in the narrative.