111982134801

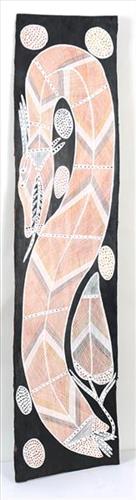

Ngalyod (Rainbow Serpent)

The rainbow serpent is a powerful mythological figure for all Aboriginal people throughout Australia. Characteristics of the rainbow serpent vary greatly from group to group and also depending on the site. Often viewed as a female generative figure, the rainbow serpent can sometimes also be male. She has both powers of creation and destruction and is most strongly associated with rain, monsoon seasons and of course the colour seen in rainbows which arc across the sky like a giant serpent. For Aboriginal people in Northern Australia, the rainbow serpent is said to be active during the wet season.

Known as Ngalyod in the Kuninjku language of western central Arnhem Land, the rainbow serpent is mostly associated with bodies of water such as billabongs, creeks, rivers and waterfalls where she resides. Therefore she is responsible for the production of most water plants such as water lilies, water vines, algae and palms, which grow near water. The roar of waterfalls in the escarpment country is said to be her voice. Large holes in stony banks of rivers and cliff faces are said to be her tracks. She is held in awe because of her apparent ability to renew her life by shedding her skin and emerging anew. Aboriginal myths about the rainbow serpent often describe her as a fearful creature that swallows humans only to regurgitate them, transformed by her blood. The white ochre used by artists to create the brilliant white paint for bark paintings, body decoration and in the past, rock art, is said to be the faeces of the rainbow serpent.

Aboriginal people today respect and care take sacred sites where the rainbow serpent is said to reside. Often certain activities are forbidden at these places for fear that the wrath of the great snake will cause sickness, accidents and even tempests. This is not always the case however and there are many rainbow serpent sites today where people may enter to hunt, fish or swim. By painting this figure on bark today, Aboriginal people are carrying on the longest uninterrupted mythological tradition in the world, which has been the subject of art and ceremony for possibly thousands of years.